|

Hume’s Tomb / A Sharper Image

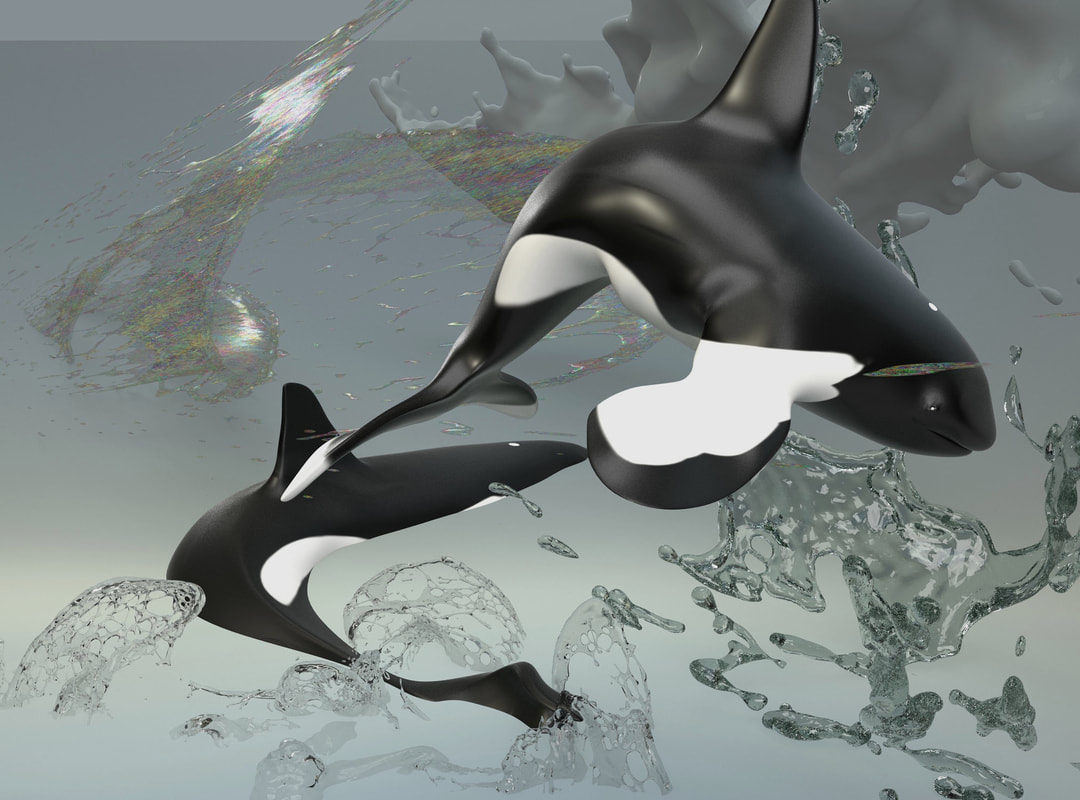

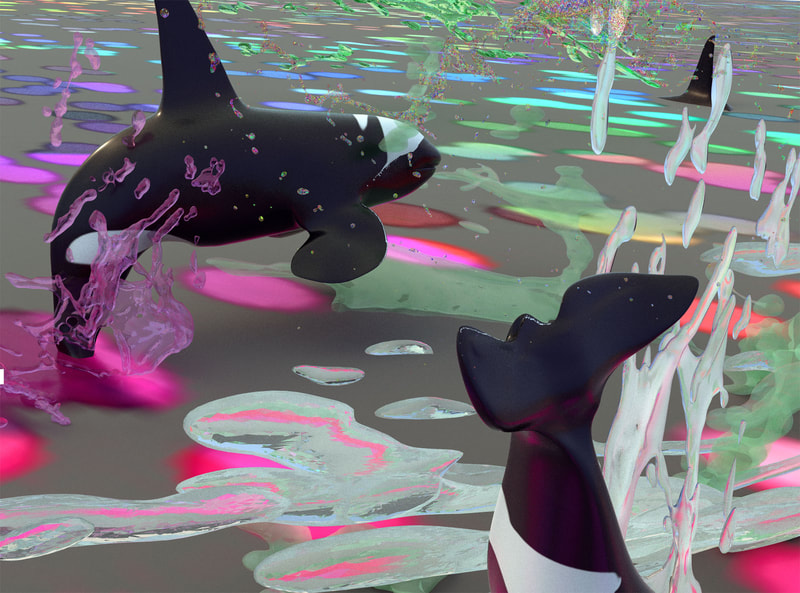

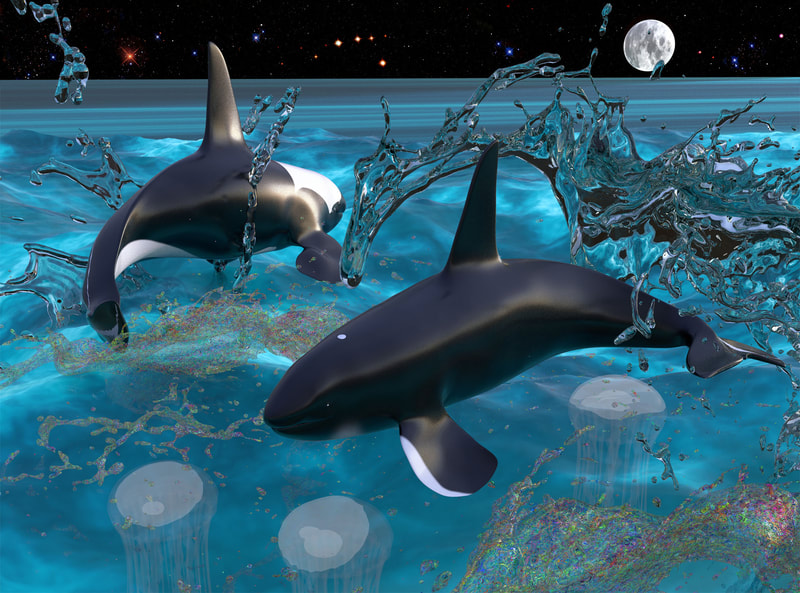

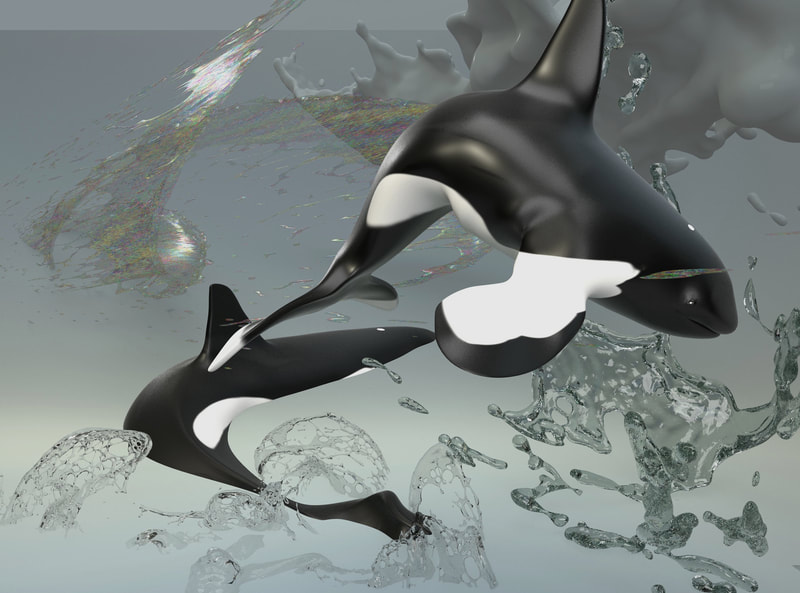

by Matthew Offenbacher February 1st - March 15th, 2019 https://www.helloari.com/~matt/ Hume’s Tomb / A Sharper Image “Hume’s Tomb” is a video about how machines know things and what they do with that knowledge. Indulging in a bit of archaeology of the digital world, the video revives Microsoft’s infamous late 1990s Windows desktop agents. In doing so, it proposes looking at today’s digital agents (such as Amazon’s Alexa) as, on the one hand, implementations of a probabilistic model of thinking first proposed by David Hume in the 1700s; and, on the other, the latest incarnation of numerous small magical creatures—such as djinn, leprechauns, elves, sprites and faeries—that embody anxieties about power, servitude, entrapment, paranoia, wish-fulfillment and control. “A Sharper Image” is a series of jigsaw puzzles that depict orca whales, the beloved Puget Sound icons who are often employed as symbols of indigeneity, environmental catastrophe, or as stand-ins for nature as a whole. The orca pictures were synthesized using a new Adobe 3D compositing software intended for product and packaging design. This software renders photo-realist images of the shimmering surfaces of luxury objects with extraordinary precision. Digital technologies have become adept at mining, storing and manipulating enormous reservoirs of data. However, there is a common misapprehension that more data leads to better understanding. These puzzles sit uneasily between the desire for ‘the whole picture’ and the suspicion that the basis for ethical action resides elsewhere. Hume’s Tomb single channel digital video, seven minutes, 2019 The video will be available for viewing and the puzzles for piecing together at cogean? in Bremerton, Washington. Additional puzzles will be located on the Washington State ferries “Kaleetan” and “Chimacum” that sail between Bremerton and Seattle. Please join us:

Friday, Feb 1, 5-8pm First Friday Opening Reception Saturday, Feb 9, 1:30-5pm Puzzle Party Saturday, Mar 9, 1:30-5pm Closing Party ~ and always by appointment ~ |

Interview with Matthew Offenbacher

January, 2019

cogean?: How do you think tech is currently influencing art in our region? Has it affected your artistic practice?

Matthew Offenbacher: This show is very much me trying to think about what the Puget Sound contributes to the rest of the world right now. And our main export is not lumber or airplanes or coffee! It’s a kind of ultra-capitalism that invents algorithms to orchestrate global flows of goods and services. We’re deep in the business of organizing data towards the end of inventing more efficient ways of organizing objects and people. Maybe by now we’re accustomed to the brutal logic that Amazon Prime uses to match digital desires to commodities on your doorstep. I think Amazon’s greatest innovation is a cultural one. It has something to do with eliding the difference between abstract data, the logical operations computers do with that data, and actual objects and lives. Trying to understand and make art about this—about the ethical and moral challenges it presents—feels like a huge undertaking, and one that we’re maybe uniquely positioned to take on from here.

c?: The works in this show have elements of both the analog and the digital; do you think of them as a pair of works that complete each other? Or something different?

I guess what I’m trying to do with my puzzles and video, and I’m just starting to figure out how to do this, is to replace dualistic ways of thinking with more complex models of the world, models I think we desperately need if we’re going to survive this fucked up time. I’ve been rereading Eve Sedgwick and Adam Frank’s essay “Shame in the Cybernetic Fold”. They argue for getting into the habit of thinking of digital and analog modes as compound, interwoven layers. Here’s something they quote from a 1970s paper by Anthony Wilden: “The question of the analog and the digital is one of relationship, not one of entities. Switching from analog to digital [and vice versa] is necessary for communication to cross certain kinds of boundaries. A great deal of communication—perhaps all communication—undoubtedly involves constant switching of this type.”

c?: What are your thoughts on Artificial Intelligence? How will it help us and how can it hurt us?

MO: I love thinking about the philosophical questions that AI brings up. How do we know what we know? How do we know what others know? What are different ways of knowing? A machine with something like self-consciousness is probably very far off, if it’s even possible. Instead, there’s a big effort now to develop machine learning technologies. These are clever pattern-recognition algorithms, linked in layers of feedback, and trained on huge data sets. I got interested in David Hume while making this show because this is pretty much how he thought cognition works—way back in the 1700s! It’s odd because we think of the Enlightenment as the “age of reason”, but Hume was very doubtful about the power of reason and logic. Instead, he considered thinking to be a method of distributing confidence in things via correlations of sensory experience, memory and emotion.

Hume died the same year the U.S. declared independence, and I think you can trace his ideas into a very American kind of pragmatism that emphasizes success in action over all else. If brains are essentially unreliable black boxes, then it’s the output that matters. The problem with this, of course, is: who gets to define a successful output? Machine learning has a huge problem with biases embedded in algorithms, like the racist Google image recognition software that was classifying photos of black people as gorillas. This bullshit happened because the people coding and deciding what to include in the training sets are soaking in the same white supremacist ideology that lets cops safely disarm white shooters while killing unarmed black children. This is American culture encoded—not some omniscient, unbiased machine making decisions.

One weird thing about digital agents like Alexa and Siri is that they’re pretty dumb. While their abilities are based on machine learning (which I don’t think ever will result in intelligent behavior) they are designed in ways to enhance an illusion of presence and self-possession. This is an aesthetic choice, a matter of interface design. I’ve been hearing stories from friends about children they know interacting with Siri or Alexa in terrible ways; they yell at Alexa, bully and taunt her. This makes me think about stories of magical beings who become trapped in objects and are forced to grant their powers to any human who happens to find that object. These stories almost always end badly for the human.

On one hand, you could see these technologies as a place to learn about and maybe radically expand our capacity for empathy. That could be a great thing, especially considering the shameful history of how the category “human” has been restricted in order to exploit certain groups of people. On the other hand—and I think this is the concern with children bullying Alexa—there’s potential for coarsening human relationships and increasing isolation, strengthening existing hierarchies and inequalities. Will these technologies be a force for democratization and freedom, or will they reinforce toxic colonial models?

c?: Can you walk us through the video, Hume's Tomb?

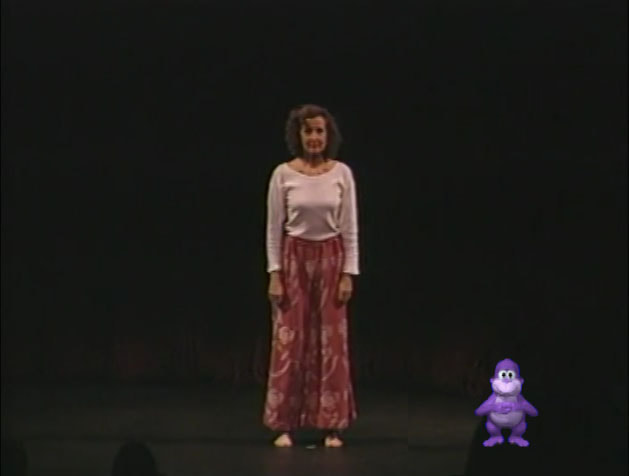

MO: I first saw this Trisha Brown dance during a class on modern and contemporary dance I took a few years ago at Cornish. I was entranced! I love this dance and I think my video is simply an attempt to try to understand why it’s so good. The first part of my video is a sort of rehearsal space where you see the digital agents (who are these little animated characters) hanging out and practicing their moves. Then, a video of Brown performing the dance (which is called “Accumulation”) appears. She’s standing alone on an empty stage. The Grateful Dead song “Uncle John’s Band” begins. She starts with a simple sequence of gestures. Then, for six minutes or so, she continuously adds a new gesture to the end of the sequence, repeating all of the previous gestures each time. In my video, the agents do their version of the dance alongside Brown.

One thing I’ve realized is that while the dance is programmatic and additive—the choreography has this machine-like logic—the effect isn’t robotic and mechanical at all. Why is that? I’m hoping an answer might pop out by having Clippy and his friends dance along. While these characters are the ancestors of Alexa and Siri, I just realized that I’m not using them as digital agents, but as puppets. They were pretty crappy agents anyway, which is why they were such a failure for Microsoft. They couldn’t do or learn much of anything. (And some of them were even malevolent. BonziBuddy, the purple ape who appears in the video, was an early version of spyware. He would secretly record private data that was exploited with targeted advertising.) They were crappy agents but they make pretty great puppets.

This makes me think of the Heinrich von Kleist essay, “On the Marionette Theater”, from 1801. He tells of a conversation with a dancer friend who argues that dancing marionettes are far more graceful than dancing humans. They are always perfectly aligned along their center of gravity, because that’s how they’re made. In addition, they are completely unselfconscious. He then tells of a trained bear who’s an undefeatable fencing partner because he’s immune to all feints and tricks, because he’s not human. The story ends with this ominous vision: “We see that in the natural world, as the power of reflection darkens and weakens, grace comes forward, more radiant, more dominating . . . But that is not all; two lines intersect, separate and pass through infinity and beyond, only to suddenly reappear at the same point of intersection. As we look in a concave mirror, the image vanishes into infinity and appears again close before us. Just in this way, after self-consciousness has, so to speak, passed through infinity, the quality of grace will reappear; and this reborn quality will appear in the greatest purity, a purity that has either no consciousness or consciousness without limit: either the jointed doll or the god.”

cogean?: How do you think tech is currently influencing art in our region? Has it affected your artistic practice?

Matthew Offenbacher: This show is very much me trying to think about what the Puget Sound contributes to the rest of the world right now. And our main export is not lumber or airplanes or coffee! It’s a kind of ultra-capitalism that invents algorithms to orchestrate global flows of goods and services. We’re deep in the business of organizing data towards the end of inventing more efficient ways of organizing objects and people. Maybe by now we’re accustomed to the brutal logic that Amazon Prime uses to match digital desires to commodities on your doorstep. I think Amazon’s greatest innovation is a cultural one. It has something to do with eliding the difference between abstract data, the logical operations computers do with that data, and actual objects and lives. Trying to understand and make art about this—about the ethical and moral challenges it presents—feels like a huge undertaking, and one that we’re maybe uniquely positioned to take on from here.

c?: The works in this show have elements of both the analog and the digital; do you think of them as a pair of works that complete each other? Or something different?

I guess what I’m trying to do with my puzzles and video, and I’m just starting to figure out how to do this, is to replace dualistic ways of thinking with more complex models of the world, models I think we desperately need if we’re going to survive this fucked up time. I’ve been rereading Eve Sedgwick and Adam Frank’s essay “Shame in the Cybernetic Fold”. They argue for getting into the habit of thinking of digital and analog modes as compound, interwoven layers. Here’s something they quote from a 1970s paper by Anthony Wilden: “The question of the analog and the digital is one of relationship, not one of entities. Switching from analog to digital [and vice versa] is necessary for communication to cross certain kinds of boundaries. A great deal of communication—perhaps all communication—undoubtedly involves constant switching of this type.”

c?: What are your thoughts on Artificial Intelligence? How will it help us and how can it hurt us?

MO: I love thinking about the philosophical questions that AI brings up. How do we know what we know? How do we know what others know? What are different ways of knowing? A machine with something like self-consciousness is probably very far off, if it’s even possible. Instead, there’s a big effort now to develop machine learning technologies. These are clever pattern-recognition algorithms, linked in layers of feedback, and trained on huge data sets. I got interested in David Hume while making this show because this is pretty much how he thought cognition works—way back in the 1700s! It’s odd because we think of the Enlightenment as the “age of reason”, but Hume was very doubtful about the power of reason and logic. Instead, he considered thinking to be a method of distributing confidence in things via correlations of sensory experience, memory and emotion.

Hume died the same year the U.S. declared independence, and I think you can trace his ideas into a very American kind of pragmatism that emphasizes success in action over all else. If brains are essentially unreliable black boxes, then it’s the output that matters. The problem with this, of course, is: who gets to define a successful output? Machine learning has a huge problem with biases embedded in algorithms, like the racist Google image recognition software that was classifying photos of black people as gorillas. This bullshit happened because the people coding and deciding what to include in the training sets are soaking in the same white supremacist ideology that lets cops safely disarm white shooters while killing unarmed black children. This is American culture encoded—not some omniscient, unbiased machine making decisions.

One weird thing about digital agents like Alexa and Siri is that they’re pretty dumb. While their abilities are based on machine learning (which I don’t think ever will result in intelligent behavior) they are designed in ways to enhance an illusion of presence and self-possession. This is an aesthetic choice, a matter of interface design. I’ve been hearing stories from friends about children they know interacting with Siri or Alexa in terrible ways; they yell at Alexa, bully and taunt her. This makes me think about stories of magical beings who become trapped in objects and are forced to grant their powers to any human who happens to find that object. These stories almost always end badly for the human.

On one hand, you could see these technologies as a place to learn about and maybe radically expand our capacity for empathy. That could be a great thing, especially considering the shameful history of how the category “human” has been restricted in order to exploit certain groups of people. On the other hand—and I think this is the concern with children bullying Alexa—there’s potential for coarsening human relationships and increasing isolation, strengthening existing hierarchies and inequalities. Will these technologies be a force for democratization and freedom, or will they reinforce toxic colonial models?

c?: Can you walk us through the video, Hume's Tomb?

MO: I first saw this Trisha Brown dance during a class on modern and contemporary dance I took a few years ago at Cornish. I was entranced! I love this dance and I think my video is simply an attempt to try to understand why it’s so good. The first part of my video is a sort of rehearsal space where you see the digital agents (who are these little animated characters) hanging out and practicing their moves. Then, a video of Brown performing the dance (which is called “Accumulation”) appears. She’s standing alone on an empty stage. The Grateful Dead song “Uncle John’s Band” begins. She starts with a simple sequence of gestures. Then, for six minutes or so, she continuously adds a new gesture to the end of the sequence, repeating all of the previous gestures each time. In my video, the agents do their version of the dance alongside Brown.

One thing I’ve realized is that while the dance is programmatic and additive—the choreography has this machine-like logic—the effect isn’t robotic and mechanical at all. Why is that? I’m hoping an answer might pop out by having Clippy and his friends dance along. While these characters are the ancestors of Alexa and Siri, I just realized that I’m not using them as digital agents, but as puppets. They were pretty crappy agents anyway, which is why they were such a failure for Microsoft. They couldn’t do or learn much of anything. (And some of them were even malevolent. BonziBuddy, the purple ape who appears in the video, was an early version of spyware. He would secretly record private data that was exploited with targeted advertising.) They were crappy agents but they make pretty great puppets.

This makes me think of the Heinrich von Kleist essay, “On the Marionette Theater”, from 1801. He tells of a conversation with a dancer friend who argues that dancing marionettes are far more graceful than dancing humans. They are always perfectly aligned along their center of gravity, because that’s how they’re made. In addition, they are completely unselfconscious. He then tells of a trained bear who’s an undefeatable fencing partner because he’s immune to all feints and tricks, because he’s not human. The story ends with this ominous vision: “We see that in the natural world, as the power of reflection darkens and weakens, grace comes forward, more radiant, more dominating . . . But that is not all; two lines intersect, separate and pass through infinity and beyond, only to suddenly reappear at the same point of intersection. As we look in a concave mirror, the image vanishes into infinity and appears again close before us. Just in this way, after self-consciousness has, so to speak, passed through infinity, the quality of grace will reappear; and this reborn quality will appear in the greatest purity, a purity that has either no consciousness or consciousness without limit: either the jointed doll or the god.”

Living with Matthew Offenbacher's Hume's Tomb / A Sharper Image

Here in the northwest, the weather is rarely bad in a dramatic sense. The in-your-face brutality of the Midwest in winter, with its similarly dramatic lows and highs of human compassion and connection, is a far cry from our usual mild winter. For us, it’s much more of a frog-in-a-pot situation. The winter isn’t that bad until you find yourself in February, all the sudden much more depressed than you thought you were, but without the resiliency that comes with the constant vigilance against the extreme elemental forces and with no countermeasures for the inevitable arrival of a dangerous point in the cycle.

It’s not all bad though, this turn inward means winter is the season of the mind, of contemplation and meditation, of puzzles of all sorts. This point in the cycle of the year was manifested at cogean? in the first show of 2019, Matthew Offenbacher’s Hume’s Tume / A Sharper Image.

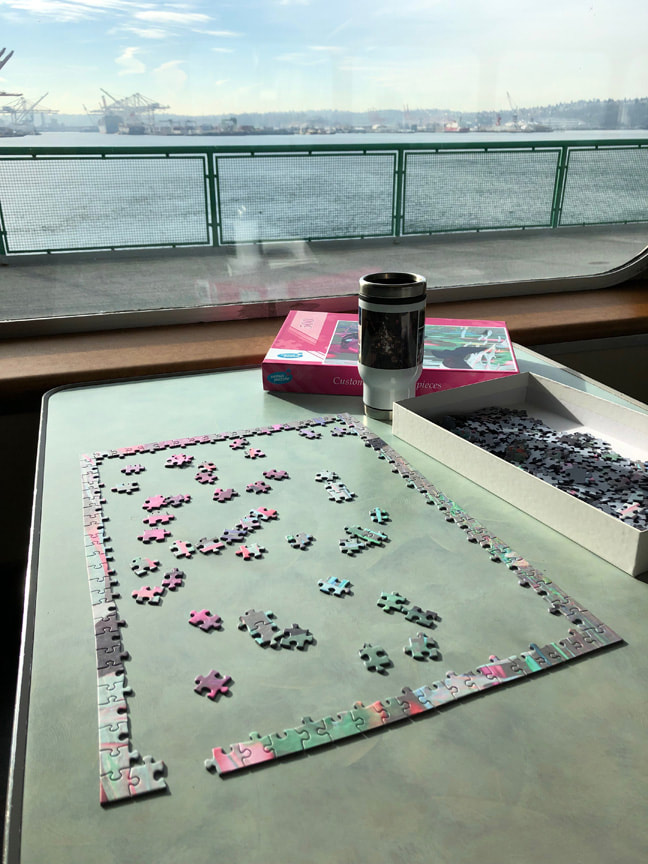

In the first room of the gallery was “A Sharper Image”, a collection of jigsaw puzzles, set out on card tables and available for assembly, others still in their boxes and wrapped in plastic, ready to purchase and take home. And as part of the recent local tradition, several of the puzzles were also placed on the ferries running from Seattle to Bremerton, available for the cooperative of people passing the time on the hour-long ride.

The puzzles themselves were made by a manufacturer in Slovakia, designed to Matt’s specification and with images that he created using an advanced digital animation software, generally intended for creating product packaging and advertising images. Matt used the software to create lush, otherworldly and almost psychedelic seascapes and underwater landscapes, each design saturated in color and slick with gloss. And all of them featuring orca whales, pristinely rendered, but then oh-so slightly pulled and twisted, their unrealness exposed. What a symbolic weight these creatures carry for us, and how do we see them when we see them from the decks of the ferry’s and whale watching boats? And how do we respond to the impacts our actions have on them? If we can create them to specification in a digital world, what then? With this work, our participation is invited, to work on the puzzles together, in commune and over time, leaving our progress for the next wave of hands and eyes.

In the second room of the gallery, a puzzle of a different sort is presented with Hume’s Tomb. A single channel video playing on a tv on the floor, the work shows footage of dancer Trisha Brown performing the piece she innovated originally in the 60s, Accummulation. The dance, performed to The Grateful Dead’s Uncle John’s Band, consists of the performer accumulating and repeating different motions, a simple dance blossoming into a full body expression. Over the top of this footage, and in companion to Trisha Brown, Matt has introduced BonziBuddy, a digital avatar from the era of Microsoft’s Clippy, programmed to dance and sing along with Trisha Brown. Not just an alternative representation of Clippy’s functionality, BonziBuddy originally acted as well as spyware, taking a look at its users financial information. Watching the piece, it’s impossible not to attempt to unlock the puzzle of the dance with your own body, nor is it easy to keep from humming the tune that the purple gorilla sings in the beginning. And again, like with “A Sharper Image”, we are presented again with the digital representation of an animal, a blending of the appearance of the natural world with the world of our creation.

The intersecting spheres of our digital and natural worlds, both in the midst of future shaping proportions, are inevitably the places we go in the darkness of the winter. And, though difficult and painful as it is to take stock of ourselves as it is, it is nonetheless important, as it is these considerations that steer us during the seasons of action. And the loving, Mary Poppins-esque trickster that he is, Matt’s work guides us to and through the difficult paths of life with sweetness, puzzles, folk music and dancing, giving us the spoonful of sugar that we need to help the medicine go down.

It’s not all bad though, this turn inward means winter is the season of the mind, of contemplation and meditation, of puzzles of all sorts. This point in the cycle of the year was manifested at cogean? in the first show of 2019, Matthew Offenbacher’s Hume’s Tume / A Sharper Image.

In the first room of the gallery was “A Sharper Image”, a collection of jigsaw puzzles, set out on card tables and available for assembly, others still in their boxes and wrapped in plastic, ready to purchase and take home. And as part of the recent local tradition, several of the puzzles were also placed on the ferries running from Seattle to Bremerton, available for the cooperative of people passing the time on the hour-long ride.

The puzzles themselves were made by a manufacturer in Slovakia, designed to Matt’s specification and with images that he created using an advanced digital animation software, generally intended for creating product packaging and advertising images. Matt used the software to create lush, otherworldly and almost psychedelic seascapes and underwater landscapes, each design saturated in color and slick with gloss. And all of them featuring orca whales, pristinely rendered, but then oh-so slightly pulled and twisted, their unrealness exposed. What a symbolic weight these creatures carry for us, and how do we see them when we see them from the decks of the ferry’s and whale watching boats? And how do we respond to the impacts our actions have on them? If we can create them to specification in a digital world, what then? With this work, our participation is invited, to work on the puzzles together, in commune and over time, leaving our progress for the next wave of hands and eyes.

In the second room of the gallery, a puzzle of a different sort is presented with Hume’s Tomb. A single channel video playing on a tv on the floor, the work shows footage of dancer Trisha Brown performing the piece she innovated originally in the 60s, Accummulation. The dance, performed to The Grateful Dead’s Uncle John’s Band, consists of the performer accumulating and repeating different motions, a simple dance blossoming into a full body expression. Over the top of this footage, and in companion to Trisha Brown, Matt has introduced BonziBuddy, a digital avatar from the era of Microsoft’s Clippy, programmed to dance and sing along with Trisha Brown. Not just an alternative representation of Clippy’s functionality, BonziBuddy originally acted as well as spyware, taking a look at its users financial information. Watching the piece, it’s impossible not to attempt to unlock the puzzle of the dance with your own body, nor is it easy to keep from humming the tune that the purple gorilla sings in the beginning. And again, like with “A Sharper Image”, we are presented again with the digital representation of an animal, a blending of the appearance of the natural world with the world of our creation.

The intersecting spheres of our digital and natural worlds, both in the midst of future shaping proportions, are inevitably the places we go in the darkness of the winter. And, though difficult and painful as it is to take stock of ourselves as it is, it is nonetheless important, as it is these considerations that steer us during the seasons of action. And the loving, Mary Poppins-esque trickster that he is, Matt’s work guides us to and through the difficult paths of life with sweetness, puzzles, folk music and dancing, giving us the spoonful of sugar that we need to help the medicine go down.