|

Hut House

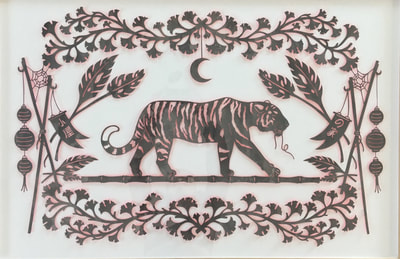

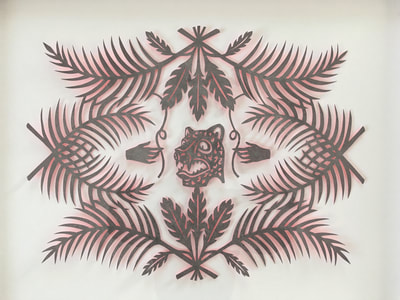

by Jessica McCourt October 5th - November 10th, 2018 www.instagram.com/empireofpaper Hut House is an exploration of creating a space for one’s self, reaching back to childhood forts, elements of magic held within nature and ornamental design that has resided within myself from an early age. Akin to auto-writing, the forms flow directly onto paper with little direction from a conscious effort, allowing a melding collection of oddities to emerge,pulled from deep within. Opening reception: Friday, October 5th, 2018, 6-9pm Artist brunch: Saturday, October 6th, 2018, 11-2pm - come out and meet / say hello to the artist! food + art! - |

Interview with Jessica

September 2018

cogean?: Where do find inspiration?

Jessica McCourt: EVERYWHERE! It’s a bit ridiculous, but the scope of things in this world that influence my work is immense. That said, the simplest, and most prevalent would be nature. Plants and animals have always been represented in my work, from paintings to paper-cuts. I love antiquarian items as well and am a collector of sorts. If I could live inside a natural history museum, I would.

c?: Was your approach different for this show than it would be at a traditional gallery space?

JM: Yes, unlike a traditional gallery space, a home space becomes immediately more personal. It is recognizable as a dwelling and so it takes on an inherent feeling of residence. Because of this, I wanted to meld the two ideas of presentation - art hanging on a wall as in a traditional gallery space, combined with objects from my own home and studio. The term "Hut House" came to mind when thinking about how the location can take on the characteristics of a childhood fort - a place where one can start to explore creation of a personal space. The nature of this type of a gallery presents less pressure to make "sellable" work. I have really enjoyed taking a different approach to paper-cutting. I'm more focused on creating an compelling space with the pieces.

c?: Speaking of homes, which artists would get an invite to your dream dinner party?

JM: That's a tough one because frankly, I might enjoy the work, but not enjoy the company. I think an evening with Allison Goldfrapp, Anais Nin, Walton Ford, Alexander McQueen and maybe one of those cats that paint. But really, who the hell knows. I'm happy to meet anyone doing creative work, human or otherwise.

Jessica McCourt: EVERYWHERE! It’s a bit ridiculous, but the scope of things in this world that influence my work is immense. That said, the simplest, and most prevalent would be nature. Plants and animals have always been represented in my work, from paintings to paper-cuts. I love antiquarian items as well and am a collector of sorts. If I could live inside a natural history museum, I would.

c?: Was your approach different for this show than it would be at a traditional gallery space?

JM: Yes, unlike a traditional gallery space, a home space becomes immediately more personal. It is recognizable as a dwelling and so it takes on an inherent feeling of residence. Because of this, I wanted to meld the two ideas of presentation - art hanging on a wall as in a traditional gallery space, combined with objects from my own home and studio. The term "Hut House" came to mind when thinking about how the location can take on the characteristics of a childhood fort - a place where one can start to explore creation of a personal space. The nature of this type of a gallery presents less pressure to make "sellable" work. I have really enjoyed taking a different approach to paper-cutting. I'm more focused on creating an compelling space with the pieces.

c?: Speaking of homes, which artists would get an invite to your dream dinner party?

JM: That's a tough one because frankly, I might enjoy the work, but not enjoy the company. I think an evening with Allison Goldfrapp, Anais Nin, Walton Ford, Alexander McQueen and maybe one of those cats that paint. But really, who the hell knows. I'm happy to meet anyone doing creative work, human or otherwise.

c?: Can you talk about the progression from illustration/painting to the cut-paper work you’re making now? Where do the practices overlap?

JM: I've always been a sketcher, drawing all the time. I moved into exploring watercolor about twelve years ago and I really took to it. The medium of cut paper had always fascinated me and I'm not really sure of the moment I was compelled to try my hand at it. Even though it is still two dimensional in nature, it felt as if I was stepping into a sculptural medium, which was completely foreign to me. The very first pieces I did were rather basic, and as I explored further, my understanding of positive and negative space relation grew. I then explored combining the two elements of painting and paper cut, creating a sort of frame out of paper to hold a painted image. I really do like melding the two together and I hope to explore more of that on a larger scale in the future.

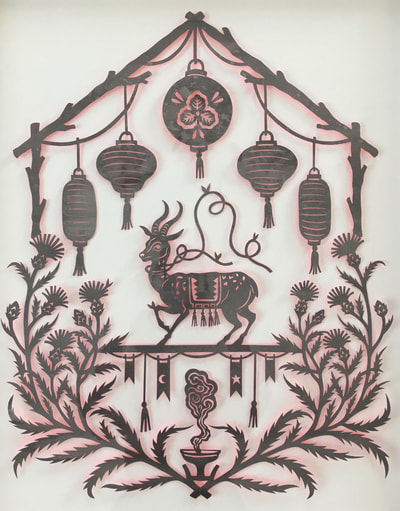

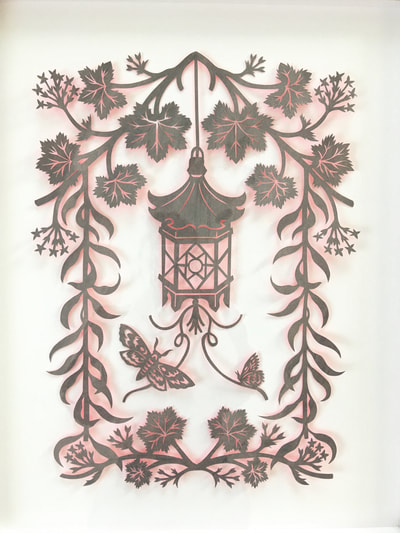

c?: Lanterns frequently show up in your work; what do they symbolize for you?

JM: I have always loved paper lanterns. There is something so beautiful about the light and design of them. The softness of the light creates an ethereal quality that is alluring. For me, they symbolize a tie to a celestial plane.

c?: What’s your favorite season?

JM: Fall. I was born in late October and it seems to fit my personality. I love the crisp air and the changing of color. It always seems otherworldly to me.

Living with Jessica McCourt's Hut House

November, 2018

The nights have gotten cold, though the days this fall have been warm, making all the deciduous trees glorious, their burning colors baked in from the fiery summer. Our magnolia tree’s leaves turned yellow with black spots here and there like overripe banana peels, before shedding them, attempting to smother the plants that thrive in its shade. Last year we piled them up in a corner of the garden in a halfhearted compost pile. This year we bagged them up, 12 bags in total. We’ve also moved the lawn furniture into the garage, drained the outdoor faucets and clipped back all the plants that need clipping (others will have to wait until their preferred time of year, later into the fall.) Our sister visited recently, and brought a cooler full of wild game hunted by our father, which now fills our chest freezer, along with the jars of stock and frozen berries. And cabinets throughout the house have been reorganized after the relaxing of systems that comes with the summer months. Finally, we are ready to settle in for the long dark months.

Still so new to the idea of being responsible for a home, we feel often like children who, in the midst of playing house, find the projects of their imaginations come to life, the vague notions of the life of adults solidified into specifics with defined edges and shadows cast. How strange to see the games of our childhood manifest in the world, the logic of it falling together only after the fact, the prophesy being only intelligible after the action has happened. Such is the magic of defining space.

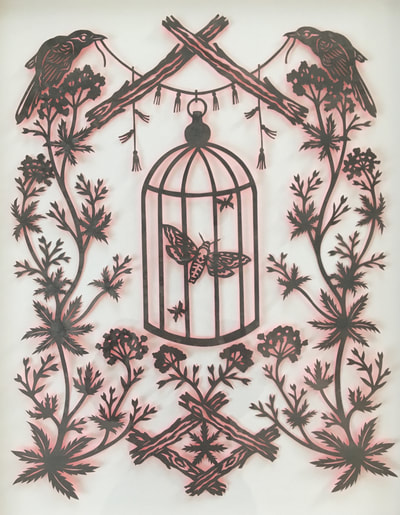

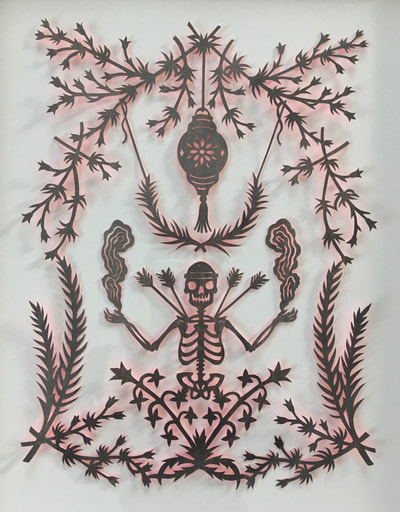

These considerations are particularly on our minds these days in reflection of Jessica McCourt’s artworks occupying the gallery rooms of our house, as she presents her show Hut House, a meditation on the fantastical worlds of our child-selves as the means of creating spaces of safety of ourselves. However, this safe space is not one occupied only by the sweetness and light of a revisionist memory that blots out the reality of childhood. In the walls hang beautifully realized papercut pieces depicting dancing skeletons, severed hands, moths in cages. Over the mantle hangs a cutout of a tiger with its teeth bared. Glowing paper lanterns hang from the ceiling, some painted. On the bookcase is a papercut light box, animal skulls, old naturist guides. In the second room are more glowing lanterns strewn on the floor, surrounding a pink and grey paper chandelier they hangs from the center of the room.

It is as though the dark phantoms of our childhoods, through the exquisitely precise craftsmanship of a mature hand, have been trapped by the sharply cut edge of the paper, floating in their frames, casting impossible light. Made all the more gentle by the colors they are rendered in, a gray-beige the same as the carpets in the gallery, and their backpainting reflecting the pink of the gallery curtains. There they hang, the paper cuts, paper chandelier and painted paper lanterns, glowing but contained—like the animal skulls brought in by the artist and placed on the shelves, trophies from the hunting of the fears of childhood.

And so perhaps, ultimately, this is an adult fantasy, that through the knowledge of repetition, of confrontation, of capturing in guidebooks the knowledge of the world, that we can somehow overcome it and be safe in our forts built of paper and reflected light.

Still so new to the idea of being responsible for a home, we feel often like children who, in the midst of playing house, find the projects of their imaginations come to life, the vague notions of the life of adults solidified into specifics with defined edges and shadows cast. How strange to see the games of our childhood manifest in the world, the logic of it falling together only after the fact, the prophesy being only intelligible after the action has happened. Such is the magic of defining space.

These considerations are particularly on our minds these days in reflection of Jessica McCourt’s artworks occupying the gallery rooms of our house, as she presents her show Hut House, a meditation on the fantastical worlds of our child-selves as the means of creating spaces of safety of ourselves. However, this safe space is not one occupied only by the sweetness and light of a revisionist memory that blots out the reality of childhood. In the walls hang beautifully realized papercut pieces depicting dancing skeletons, severed hands, moths in cages. Over the mantle hangs a cutout of a tiger with its teeth bared. Glowing paper lanterns hang from the ceiling, some painted. On the bookcase is a papercut light box, animal skulls, old naturist guides. In the second room are more glowing lanterns strewn on the floor, surrounding a pink and grey paper chandelier they hangs from the center of the room.

It is as though the dark phantoms of our childhoods, through the exquisitely precise craftsmanship of a mature hand, have been trapped by the sharply cut edge of the paper, floating in their frames, casting impossible light. Made all the more gentle by the colors they are rendered in, a gray-beige the same as the carpets in the gallery, and their backpainting reflecting the pink of the gallery curtains. There they hang, the paper cuts, paper chandelier and painted paper lanterns, glowing but contained—like the animal skulls brought in by the artist and placed on the shelves, trophies from the hunting of the fears of childhood.

And so perhaps, ultimately, this is an adult fantasy, that through the knowledge of repetition, of confrontation, of capturing in guidebooks the knowledge of the world, that we can somehow overcome it and be safe in our forts built of paper and reflected light.